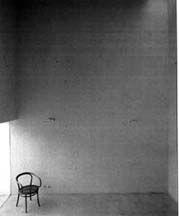

Fig. 1. Jean Nouvel: Cartier Foundation for Contemporary Art, Paris [13]

Published in: Proceedings of ACSA International Conference. Copenhagen, Denmark: Royal Academy of Fine Arts School of Architecture, pp. 66-71 (1996)

© copyright 1996 Julio Bermudez & Robert Hermanson. All rights reserved.

Note: PARA UNA VERSION EN ESPAÑOL: DOCUMENTO PDF (Artículo en Morphia 1999). DOCUMENTO EN LINEA: Reflexiones Sobre la Arquitectura Contemporanea (1997)

...

Our jobs, entertainments, and relationships increasingly demand less and less from our bodies. Neither muscle nor even presence are truly important in more and more tasks. From ATM machines to television to telecommuting to the internet, contemporary life depends on the absence of the body or, better said, in substituting its presence by means of information (i.e., non-material) technology.

Late 20th Century consumer society, that supposedly celebrates materialism and fully satisfies the body, actually devalues materiality and the corporeal as even its most desirable goods become evanescent items whose values begin to disappear immediately after purchase (as they are used up, worn out, or fall out of fashion). Consumer society only values the source, the act and/or the reason for acquiring (or enticing to acquire). Not surprising, consumerism has necessarily evolved into a media culture whose purpose is the continuous (re)creation of needs that are obtained via information and satisfied through further consumption. The resulting information age only accelerates the displacement of the material, the real, and the body.

Contemporary civilization gives little room for interpretation in this matter. In today's world, manufacturing has lost its importance to service and information. Construction cannot compete against the speculative stock market and the ephemeral MTV. Craft, assembly, stability, attachment, presence, and detail continue to recede as image, juxtaposition, fluidity, detachment, surface/interface, and impression take over. All this indicates that the architectural act is moving from materialization to visualization. The language of texture is being taken over by the language of images.

And yet, as we detach ourselves more and more from the materiality of life during our waking time, the more we are attracted to it. For instance, the glorification of the body, the huge popular draw of sports (albeit mediatized), the fashionable physical fitness and healthy lifestyles, the mystification and mythification of physical beauty, youth and sex, and the use of legal or illegal drugs to enhance the sensorial experience of bodily existence indicate the presence of some social/personal mechanism of compensation.

Quite simply, we cannot shut down what we are: incarnated, corporeal beings. Thus we find ourselves in the midst of a struggle: the ancient, primordial calls of the body and its instincts (the unconscious) collide with the cultural demands of detached rationality, immaterial action, digital production, and mindless consumption. Tectonics "smashes" into the ethereal.

In architecture, this issue increasingly dominates contemporary reflections. [2] Is it possible, for instance, to honestly maintain a material and traditional understanding of architecture in a world increasingly dominated by disembodied virtuality ? When the visual appearance of something is more important than its actuality, when the seeming is more important than the real thing, is there room for tectonics? Instead of attempting to answer these questions, we have chosen to present arguments and examples describing what we see as different directions at work in the struggle of contemporary architecture to deal with the forces of virtuality and tectonics. Implicit in this position, so beautifully expressed in Kurosawa's film Roshomon, is that "there is no single truth, no single explanation; even observation itself is open to scrutiny." [3] This inclusive and pluralist viewpoint implies a rejection of dualism and its forced constructions and choices. We will briefly elaborate on this point before proceeding with the architectural discussion.

...

...

Inevitably trapped in the prison of discursive language/thought, we are to use its binary constructions to establish a conceptual terrain upon which we can engage in a reflection that moves back and forth between these structures. This approach, however, neither defines the problematic as dualist nor does it attempt to resolve the tension in some final synthesis.

Kisho Kurokawa's interpretation of symbiosis appears very useful here. [6] According to Kurokawa symbiosis implies a relationship of mutual need between different parties in which there still could be competition, opposition, and struggle as long as there are common elements and values that keep the interaction going. He adds that "the concept of symbiosis is basically a dynamic pluralism. It does not seek to reconcile binomial opposites through dialectics ... " [7] but instead implies situations and products that are ambiguous, vague, chance-driven and plagued with multivalences and contradictions.

We are thus to examine the seemingly opposing sides of virtuality and tectonics with an understanding that they imply and need one another and may act as potential parents of multiple parallel, coexisting, and at times conflicting offsprings. Accepting this dynamic relationship between language based categories will shed a post-dualist light on the subject under scrutiny.

...

...

This cultural situation has not yet been fully expressed architecturally. The great majority of our built environment continues to be designed and made following an ideological agenda that precedes and thus does not acknowledge the contemporary world. From this standpoint, there is the need, indeed the duty of architecture to express today's zeitgeist. This position would support the projectation and construction of buildings that bring the qualities of a media culture into the quite actual realm of the built. This 'creative' exportation of the logic, nature, and appearance of the virtual into physical reality would make people experience the hidden but quite concrete effects of virtuality in actuality. The purpose of such an architecture would not be just aesthetic but more importantly critical. Architecture would put in sight that which is out of sight by expressing the transience of our world of simulacra. But how? As Tschumi asks:

...

Fig. 1. Jean Nouvel: Cartier Foundation for Contemporary Art, Paris [13]

Fig. 2. Mehrdad Yazdani: CineMania Theatre, Los Angeles [14]

The metaphor of screen is carried further when the wall becomes a transmitter of electronic (or other) information systems and therefore adopts a state of continuous metamorphosis. This challenges our sense of space and subverts the place-making functions that architecture has historically provided. A true architecture of screens transcends its own physicality by offering buildings of a multi-dimensional character. Space and form are forgotten for the sake of what appears on the surface. Hence, the traditional fixed "whereness" of architecture is transfixed to changing virtual localities. This does not come at a great price though. After all, living in a culture of the simulacrum means to leave substance and depth behind for the sake of appearance and surface. [15] Mehrdad Yazdani's L.A. CineMania Theater and Coop Himmelblau's UFA Cinema suggest possible architectural iterations.

Ultimately, the logical locus of transience architecture resides neither inside nor outside the building, not at the skin's surface, not even on the computer screen. Rather, it exists within a series of virtual territories removed from tectonics, materiality, the body. The ultimate transience architecture must migrate from reality to cyberspace. This radical act requires a complete redefinition of architecture [16] that totally challenges and affects our own sense of being.

Transience architecture, whether in its mild or more radical incarnations, defies our ontology and in doing so fosters critical reflection. Hence, from some quarters, there is a call for resistance, the need for what may be termed "presence" architecture. [17]

...

...

Paul Valéry, in his essay "Some Simple Reflections on the Body", [22] observes that in order to really understand our corporeality we need to acknowledge a kind of nonexistence. This suggests that there are primordial or pre-existent notions that form our way of being, the sensorial aspects Ñ hearing, sight, the tactile Ñ those phenomena that contain no cultural meaning (if indeed that is possible) yet share an universality. From this perspective, this pre-(and hence cross-) cultural foundation constitutes the beginning of human presence and of architecture itself. Louis Kahn unmistakably talked about such an architecture of beginnings and the need to sense "Volume zero. Volume minus one." This foundation also explains why, despite its being anchored to the present, presence architecture may achieve transcendence. Kahn referred to this when he thought of his own buildings as eventually transcending their own zeitgeist and becoming functionless, as existing purely in and of themselves; thus, his fascination with ruins.

...

Fig. 3. Alberto Campo Baeza: Garcia Marcos House in Madrid, Spain [23]

...

Although there are examples of presence architecture in history (Barragan, Kahn, Scarpa), these architectures were never intentionally produced to balance or provide an alternative to our culture of speed, simulation, and fragmentation. Contemporary architectural work related to presence is diminishing in favor of the sexier, media driven venues of simulacra. Thus it is interesting to see architects such as Campo Baeza, in the West and Ando, in the East continuing the process of connecting with the purely sensorial, tactile qualities of the analog, real world. But again, these productions are not conscious responses to a culture of transience. Hence, we wonder what type of architecture could be generated by seeking to creatively resist the overwhelming forces of our time.

...

...

The human body is a hybrid based on symbiotic relationships that defy any clear-cut dualist differentiation. For instance, the mind, a recent evolutionary event, has been essential in the survival of the body. Without thinking (or "real virtuality" as Sanford Kwinter calls it [25] ), there would probably be no Homo Sapiens. The mind and the body require each other to unfold and deliver what we know as a human being. Their symbiosis is so strong that the malfunctioning of one dramatically affects the other. Jung and others [26] have shown that consciousness is a synergistic emergence out of unbreakable (i.e., symbiotic) physical and psychical functions (e.g., thinking, feeling, intuiting, sensing). Dewey and Whitehead have proven using philosophical and scientific arguments that it is misleading to dissect the human experience in dualist terms. [27] In turn, Mearleu-Ponty and Johnson have refuted any hope of Cartesian mind-over-body dualism by showing how the phenomenology of the body has an essential impact in shaping thought. [28] All these and many other works point out that:

...

...

Following the lessons of the body, architecture may express the schizophrenic condition of postmodernity by (a) blurring the difference between materiality and virtuality to the point of being an indistinguishable fusion --a true hybridÑ or (b) juxtaposing these opposites in such a way that while preserving their identities the resulting architectural order defies being broken down Ña symbiosis.

The first approach considers that presence and transience architectures might be viewed as "parents" in a genetic process. The resulting "child" -- the hybrid, is in fact a fusion, very much like the DNA genetic processing that takes place in procreation. The hybrid condition suggests a state of liminality that is neither material nor virtual Ñ rather a kind of tectonic-virtual suspendedness. The question remains, however. Is a hybrid architecture really possible? Observing the present state of affairs no models come to mind that truly represent this notion. Is this perhaps because we, in the West, are inheritors of the dualistic Cartesian division of mind and body? On one hand our present ideological/technological dependence on specialization and categorization indicates that we exist in a highly fragmented world that negates the fusion of the real and the virtual. On the other hand, at least historically, we might say that other cultures and zeitgeists (i.e., the Byzantine, for example) were able to do so, whether conscious of the fact or not.

...

Fig.5. Cefalù. Apse mosaic in cathedral, 1148 BC. [34]

The second approach considers that presence and transience architectures remain as distinct -- in a state of symbiosis. Here the notion of boundary and threshold prevails. Kurokawa talks about his house as a symbiotic place in which he has the tea room (and its concomitant ceremony) next door to his computer room. [35] He needs to move back and forth between these two rooms in order to maintain a dynamic pluralism. Here, the experiential nature of architecture serves as the threshold, the common element that connects these seemingly dissimilar entities. As depending on a threshold, this architectural order is also paradoxical [36] and therefore maintains a symbiotic relationship rather than a dialectic one. Nevertheless, the fact that two situations clearly are present suggests that the symbiotic condition provides a more acceptable model for the present cultural zeitgeist.

...

...

...

...

[2] See for example: Peter Eisenman, "Visions Unfolding. Architecture in the Age of Electronic Media" in A.Papadakis, G.Broadbent & M.Toy, eds., Free Spirit in Architecture (London: Academy Editions, 1992) pp.88-91. Jean Nouvel, "Jean Nouvel 1987-1994", El Croquis (Madrid, 1994). Hani Rashid & Lise Anne Couture, Asymptote. Architecture at the Interval (New York: Rizzoli Internationl Publications, 1995). Bernard Tschumi, Event-Cities (Praxis) (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1994). Robert Venturi, "Sweet and Sour," Architecture (May 1994): 51-53

[3] Marc Treib, "Tokyo Real and Imagined" in Susan Yelavich, ed., The Edge of the Millennium (New York: Whitney Library of Design, 1993) pp.88-98, quote p.88

[4] David Bohm, "Imagination, Fancy, Insight, And Reason In The Process Of Thought" in Shirley Sugerman, ed., Evolution Of Consciousness (Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press,1976). Fritjof Capra, The Tao of Physics (Boston, MA: Shambhala Publications Inc., 1991). Martin Heidegger, What is Called Thinking? (New York: Harper & Row Publishers, 1968). Chogyam Trungpa, Cutting Through Spiritual Materialism (Boulder, Colorado: Shambhala Publications Inc., 1973). Jacques Derrida, Dissemination.. Translated by Barbara Johnson (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990)

[5] John Dewey cited in Larry A. Hickman, John Dewey's Pragmatic Technology (Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1990) p.154

[6] Kisho Kurokawa, The Philosophy of Symbiosis (London: Academy Editions, 1994)

[7] Ibid., p.74

[8] Transient comes from the Latin trans-, over, accros + ire, to go. Transience: "the state or quality of being transient." Transient: "passing away with time, transitory, fleeting. Changing very quickly so as to not apprehend or make apprehension difficult." (The American Heritage Dictionary of English Language. New York: American Heritage Publishing Co., 1973)

[9] Tschumi, ibid., p.367

[10] Julio Bermudez, "Aesthetics of Information: Cyberizing the Architectural Artifact," in Proceeding of the 5th. Biennial Symposium on Arts and Technology (New London, Connecticut: Connecticut College Center for the Arts and Technology, 1995) pp.200-216

[11] Terence Riley, Light Construction (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1995)

[12] Marshall Berman, All That is Solid Melts Into Air (New York: Penguin Books,1982)

[13] Light Architecture, ibid., p.55

[14] Light Architecture, ibid., p.103

[15] Mark Taylor & Esa Saarinen, ibid.

[16] On this subject see: John Frazer, "The Architectural Relevance of Cyberspace," AD Profile #118: Architects in Cyberspace (1995) pp.76-77. William Mitchell, City of Bits (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1995). Novak, Marcos, "Liquid Architectures in Cyberspace," in Michael Benedikt, ed., Cyberspace. First Steps (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1991) pp.225-254

[17] Little has been written on this subject as we have been fascinated by the novelty of transience and simulacra. However, all of us have also heard the counter-arguments that are perhaps most succinctly summarized by Paul Goldberger, "Cyberspace, Trips to Nowhere Land," The New York Times (Oct.5, 1995), pp.B1-B4

[18] Susan Yelavich, "Setting the Stage for the Third Millenium," in Susan Yelavich, ed., The Edge of the Millennium (New York: Whitney Library of Design, 1993) pp.11-14, quote p.14

[19] Present comes from the Latin praesens: to be before one, be present; prae: in front of + esse: to be (ibid.) 20. This is almost a counter-argument to one that Italo Calvino makes about Lightness. It is the very "friction" (i.e., "gravity", "weight") of reality that awakes us to our existential and reflective condition. Italo Calvino, Six Memos for The Next Millennium (New Yor: Vintage Books, 1993)

[20] This is almost a counter-argument to one that Italo Calvino makes about Lightness. It is the very "friction" (i.e., "gravity", "weight") of reality that awakes us to our existential and reflective condition. Italo Calvino, Six Memos for The Next Millennium (New Yor: Vintage Books, 1993)

[21] Luis Barragan once said that "all architecture which does not express serenity, fails in its spiritual mission." Cited in Clive Bambord Smith, Builders in the Sun (New York: Architecture Book Publishing Co., 1967), p.54

[22] Paul Valèry, "Some Simple Reflections on the Body," in M.Feher with R.Naddaff and Nadia Tazi, eds., Fragments for a History of the Human Body (Part Two) Ñ Zone 4 (New York: Urzone Inc, 1989) pp.395-405

[23] AD Profile # 110: Aspects of Minimal Architecture (1994) p. 31

[24] Ibid., p. 6

[25] Sanford Kwinter, "On Vitalism and the Virtual," Pratt Journal of Architecture: On Making (New York: Rizzoli, 1992)

[26] Rudolf Arnheim, Towards a Psychology of Art. Collected Essays (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1966). John Dewey, Experience and Nature (La Salle, Ill: Open Court Publishing, 1965). Wilhelm Dilthey, W. Dilthey: Selected Writings. H.P. Rickman, ed. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1976). Howard Gardner, The Quest for the Mind: Piaget, Lèvy-Strauss and the Structuralist Movement (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1973). J. Jacobi, The Psychology of C.G. Jung (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 1962).

[27] John Dewey, Ibid. See also his Art As Experience (New York: Wideview/Perigee Book, 1934) and Alfred North Whitehead, Alfred North Whitehead, His Conceptions on Man and Nature. R.N. Anshan, ed. (New York: Harper and Brothers Publishers, 1961)

[28] Maurice Mearlau-Ponty, The Structure of Behavior (Boston: Beacon Press, 1963). Mark Johnson, The Body in the Mind: The Bodily Basis of Meaning, Imagination and Reason (Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 1987)

[29] Kisho Kurokawa, ibid., p.74

[30] John Dewey quoted in Larry Hickman, ibid., p.xii

[31] Karen Frank, "When I enter Virtual Reality, What Body Will I leave Behind?" AD Profile #118: Architects in Cyberspace (1995) pp.20-27, quote p.20

[32] Jean Baudrillard, ibid. Fredric Jameson, Postmodernim or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1992)

[33] From the Latin schizo-phrenia,"split mind". Schizophrenia: 1. a psychotic disorder characterized by loss of contact with the environment by noticeable deterioration in the level of functioning in everyday life. 2. the presence of mutually contradictory or antagonistic parts or qualities (ibid.)

[34] David Talbot Rice, Byzantine Art (Middlesex, England: Penguin Books Ltd., 1968) p. 210

[35] Kisho Kurokawa, Ibid.

[36] Mircea Eliade; The Sacred and The Profane (New York: Harper & Row, 1961)

...